One thing we’ve all gotten used to over the past decade is the never-ending need to authenticate ourselves. Be it KYC to get through the door, or OTP to transact once in - the checks, we’re told, are a necessary inconvenience for safe passage to global e-commerce. The logic makes sense - curbing fraud is good for business, and by extension, its customers. As we enter 2024 there is a growing realisation however, that trust is conspicuous by its absence when the boot finds itself on the other foot - and it is our bank or service provider that requires something of us. We can all tap into the uncertainty of a message or call that leaves us unsure of what's what, or most critically who’s who, in the face of a potential scam. Where is the guarantee of authenticity now? Maybe there’s just no money to be made in affording us the basic protections against being defrauded on our own time and dime? A cynical view, perhaps. But if true, where to from here?

The emerging threat

If 2020 to 2022 will be etched into the history books as the COVID Years, there is an argument to be made that 2023 will go down as the Year of the Scam. Whilst SARS-CoV-2 successfully infiltrated the population through infection and injection; scammers leveraged a simple yet effective modal to proliferate their societal virus - impersonation. What is most concerning is their best is yet to come. Weapons of such warfare have just received an upgrade, the all-seeing all-powerful artificial intelligence. AI we’re told will leave us not just dealing with fakes, but deep fakes, which hints at a future where we’ll quickly find ourselves desperately out of our depths.

Maybe the right starting point is to ask how has this opportunistic yet growingly sophisticated bunch of scoundrels managed to generate an income greater than that of Switzerland, and just a shade less than arabian power house Saudi Arabia? Despite scams often relying on the impersonation of loved ones or those in need, the vast majority of the $1.4 trillion (with a T!) ill-gotten gains prey on our inability, as consumers, to spot the fraud from the familiar when we receive a Spoof Sunday Special from Amazon and the likes.

Sounds like there should be a simple fix right? Use communication that allows businesses to securely identify themselves to us, their intended recipient. Problem solved. Oh if it was only that simple. We’ve seen a raft of cumbersome solutions designed to protect messages of value coming our way - Secure Mail in the financial services sector, the poster boy of friction-full attempts to coalesce enterprise-grade security and consumer experience in the pursuit of a safe interaction. Turns out, requiring login to access most content crosses a threshold that makes the juice just not worth the squeeze. Lesson learnt - tools generating assurance for us as a by-product are not going to cut.

Seemingly without a secure scalable alternative we find ourselves asking two old friends to evolve - the ever reliable Email, revered for its accommodating attachments and fine threads and the unassuming SMS, boasting enviable open rates (98% is a pretty good percentage of anything) across any device - both of whom have struggled to make senders known to recipients since the beginning of time. The vigilant have habitualised the Googling of email domains and cross-checking of Caller IDs - but surely this can’t be the failsafe way to bring digital trust to the communication we receive?

The lay of the land - if you know what you’re looking for…

Innovation to secure these channels has been a mixed bag of success at best, and is often dependent on who in the scam food chain you’re asking. Email protection has been rolled out in the shadows since the year 2000, DKIM, SPF and DMARC have seen skewed benefits for diligent organisations and their own legitimate communications - offering scant protection against impersonation executed against the masses. Authentication in this context is not a zero sum game. Scammers play by a different set of rules.

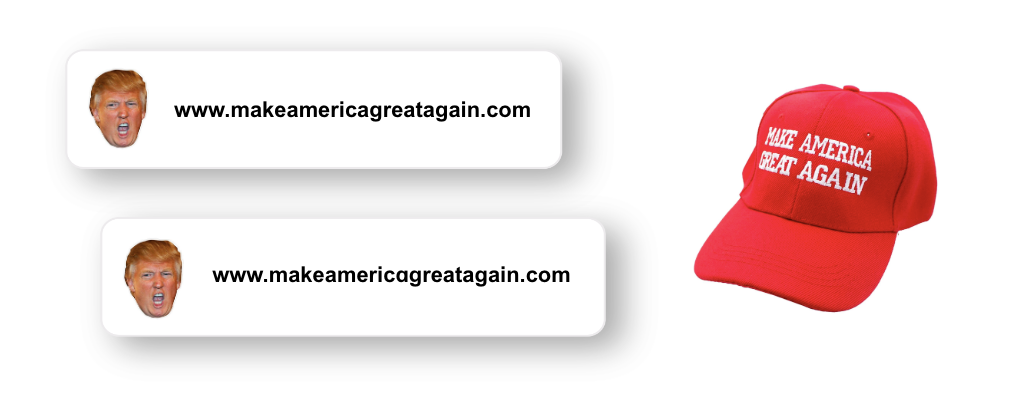

Fancy yourself as an amateur impersonation spotter? See if you can spot the difference between these two fictional Donald Trump campaign websites:

The success of the playfully acronymed BIMI, championed by the who’s who of the email ecosystem, is sadly best gauged by no-one being sure of the assurances it provides. Did you know that an email showing a company's official logo in Gmail is more than just a marketing play? Time will tell whether assured branding will enter our cultural-consciousness for authentic mail, however, its laboured adoption is in no small part down to mail monster Microsoft slow rolling its support. By excluding vast swathes of us simply based on our choice of email provider it's a non-starter for businesses wishing to afford all customers a comparable level of protection.

Speaking of compatibility, SMS has itself seen a ‘device-ive’ war in recent years, with IoS and Android offering up differing probes and protection for our short-message inbox. One of the most promising initiatives, Google’s Verified SMS, looked to offer companies and consumers a similar level of brand identification as BIMI, however, they quickly pivoted toward SMS’s slightly younger and richer (experience for the recipient that is) alternative RCS messaging. A bet on the future that sadly leaves us having to procure our own protection to fend off the 3.4 billion smishes (I hope you can make that a noun) in daily circulation. Add this to the new trend of our favourite apps requesting us to “Click and Accept” our role as honorary ‘Scam Sniffer’ and it’s not surprising that our desire to engage digitally is starting to wane.

The latest roll of the dice is to offer the safety we seek behind the authenticated walled-garden that is our banking and ecommerce apps. Messages doth flow unabated in these noisy echo chambers, the fact we’re only reading 1 in 4 of missives however has marketing and fraud teams asking if their efforts to engage and protect us are even landing. Problems with a One Channel Policy are not just limited to mobile apps - ask an ardent WeChatter whether their bank's WhatsApp for Business channel is the solution and you'll quickly see what a creature of habit looks like. Centralised verified accounts offer promise as a foundation for interactions we can trust but the silver bullet will need to protect all messages as equals. Such a challenge may need a very different approach.

We regulate any stealing of his property (we’re damn good too)

History tells us national threats call for nationwide responses. So dutifully into the trust-vacuum have stepped a raft of higher powers to help us discern Peter from Paul - pick your bad guy in this scenario. And let’s be honest, the call-to-action was loud and clear in light of scam losses reaching unsustainable levels for many economies: Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia and Vietnam finding themselves losing over 2% of their equivalent GDP to e-bandits. Even Singapore, so often opined for its high-trust economy, found itself haemorrhaging $4,031 on average per citizen, an unwanted first place if ever there was one. Phishing attacks more than doubling every year since 2019 quite simply forced regional governments to kick into gear.

The general approach has seen unregistered SIM cards stripped from national networks, in the belief that swindlers won’t go phishing with a number linked to their identity. Vietnam leant on this limiting factor, only allowing calls or texts from numbers on their national database whilst tightening up their KYC checks for corporate senders. The Philippines followed a similar approach but additionally blocked individuals' ability to send the much vilified clickable links. Malaysia mandated Telco’s to block all SMS containing links, no excuses, whilst Australia turned their attention squarely to system-generated messages, installing gateway gatekeepers - no verified Sender ID, no transit. The impact across the board - less spam hitting our devices. Yet we still find ourselves relying on the perfect execution of these upstream checks and balances. To its credit Singapore’s SSIR initiative has made an attempt to let us know if something is a ‘Likely Scam’ but a quick look under the hood and you’ll see ‘Likely Unscribed’ is just as ‘Likely’ for many messages finding themselves in the dog box.

What we have is a first phase of imperfect approaches that see Digital Trust as a service to, rather than a collaboration with, those who need safeguarding. Common wisdom: avoid single points of failure. 3,500 scam messages slipping through the net in Australia is a timely reminder that mistakes will be possible, if not expected, when relying on a single choke point to stem the tide. Top down thinking, much like the frameworks and protocols before it, looks to deliver trust rather than earn it. Maybe it’s time for a fresh approach for phase two - where consumers have the right to protect themselves?

A new paradigm, of sorts

Lessons from the past are often a good starting playbook for the challenges ahead. The most comparable war is actually being waged in parallel against corporate data the world over, causing a shift in approach by the cybersecurity industry writ large. The concept of a Zero Trust Architecture is now in vogue, demanding that all assets, applications and services are vigilant in the face of both internal and external threats. The requirement: validation of anyone, anything, all the time across a digital interaction. An Everything, Everywhere, All At Once of sorts. Could such a risk-intolerant approach be applied to communication - requiring a message to identify itself and its content each and every time if asked? Hold that thought.

There seems also to be inspiration to be drawn from the global response to a very human challenge - the obesity crisis (bear with me on this one). With nearly a billion people requiring a radical shift in behaviour we started by attacking the pathogen: bad calories in the system. Analogous to the recent spam clearout perhaps? What's hopefully instructive is what came next. With calories under control we moved to empower people with tools - the traffic light system, a shining beacon - helping us to verify the content of our food. Building resilience became about making better decisions with the right information, a proposition perhaps we can apply to communication.

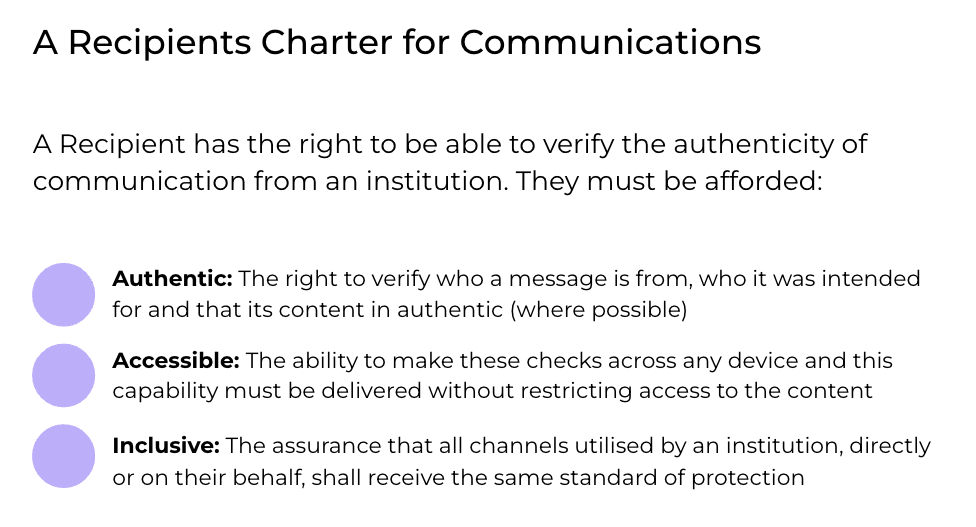

The optimistic among us believe these lessons and legacy limitations point to a framework for empowered decision making in the face of scams - A Recipients Charter if you will:

A healthy shopping list no doubt but an achievable one in light of the ingredients we have to work with. Singapore’s lead to sure-up mobile app standards is a move that, if effectively executed domestically and abroad, will form a critical foundation for the future. Secure smartphone apps offer up the dual promise of safe in-app experiences and a verifier-of-record for a broader set of digital interactions. A simple check can now displace the threat of misdirection and impersonation across any channel. Necessity may truly be the mother of invention and save the day.

Trust in the process

Whatever comes next will bring necessary friction for the consumer. Yet any scam victim will attest this is a small price to pay for protection. Behaviour change theory teaches us we need motivation, opportunity and capability to move a population, so a few billion scam-weary mobile-first citizens should have the first two requirements covered. Now we must deliver the capability. Digital Trust can win-out in the face of online threats, the critical next step is to acknowledge that it always takes two to tango.

.svg.png)

_Full Colour.png)